What I've been doing at Europe Endless #2

Nigh is the time to switch

your bookmarks.

MA is the New BAI think I’ve complained about this trend before. MA programs are used to cull prospective students, without giving them resources to do serious research–without giving them a taste of what a real doctoral program is like–just rushing them out and collecting their cash. Students who take that additional one year to add an MA to cap their undergraduate career are being short-changed, especially since they’ll have to do it all over when they start a PhD program.

Where are the Historians of Popular Political Discourse?Ben Johnson sent this down the pipe at H-Borderlands:

The Mexico-US border has been all over the news recently, what with the proposed border fence and US congressional debate over immigration. Yet H-Borderlands remains muy, muy tranquilo.

I’m wondering if we can jump-start a discussion so that those of us subscribed can take advantage of our collective wisdom. And contemporary debates actually prompt my question: what role could the “new” borderlands history play in informing contemporary debates in North America about borders and border enforcement? I see economists, political scientists, scholars of immigration, and sometimes legal experts interviewed extensively in recent news coverage, but can’t think of a single borderlands historian who’s been a talking head in major news coverage. What does that say about our field?

Good question, but it could also be generalized. Why have historians, as a group, remained silent? Why have generic arguments been made about the immigrant experience rather than zeroing in on the place of Latinos/Latinas (especially Cubans, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans) *** in American history? Why are those specific groups boxed into the immigrant experience? And why has so little effort to put current immigration to the US, legal and illegal, in global context?

*** If Scots suddenly clamored to come to America, we’d hear some arguments about cultural compatibility or pre-adaptation. Yet these three communities, by their historical presence, offer a portal to the assimilation of groups coming from Latin America.

A Democratic Style, A German StyleWhy did Germany rebuild its cities as it did, with such unrelenting modernism? This question keeps resurfacing as cities decide to replace buildings from the postwar era with those that reflect earlier historical eras. I’ve found this but of nostalgia problematic, failing to appreciate the lacuna caused by the Second World War. Hermann Glaser’s The Rubble Years: The Cultural Roots of Postwar Germany, 1945-1948 puts some of these issues into perspective, mining the brief moment immediately following the war.

In light of the devastation of the war, it was estimated that 6.5 million apartments were needed. “Rebuilding? Technologically, financially impossible, I tell you. What do I say? Psychologically impossible! However, it is possible to build simple rooms on the present foundations and out of salvageable debris . . . bright rooms in which a simple law, equal and understandable for all, is discussed and decided upon . . . no small print . . . no embellishment. Rise, up, lawyers and architects! Plan and design models, rooms of pure, simple clarity and power . . . rooms in which our children and grand- children can follow honorably and freely the universally accepted law!” This Passage Comes from Otto Bartning’s Ketzerische Gedanken am Rande der Trümmerhaufen (Heretical Thoughts at the Edge of the Rubble Heaps), which characterizes the mood of the survivors who experienced, after a total war, total defeat. The dominant mood was one of despair, pessimism, and resignation. In almost every city, however, people began to work on restoration plans based on more optimistic premises

The mood in postwar Germany was understandably dismal. People returned home to find literally nothing. The question of how to continue to live was inextricable linked to the question of where to live. Moreover, Germans were uncertain of their national future, having values shattered in a few years. Perhaps it is obvious that the new architectural style would reflect necessity and humility. Modernism seemed to answer the spiritual need to create distance with the past and repent for it.

In [Walter Gropius’s] lectures, he re-installed the idea of the ‘Bauhaus’ … .The socially conscious architecture, once expelled from Germany, was brought back to a bewildered Germany as a symbol of freedom and individuality by one its most prominent representatives. The modern architecture was supposed to represent and mirror the honesty, transparency, and openness of the young country. Its light, eager, liberal, and international style was completely focused on the Progress of technology and civilization, and expressed the social and utopian ideal of equal housing. It was opposed to provincialism, folkishness, monumentalism, and historism, especially since National Socialism favored these forms of architecture.

All cities took the opportunity to reform their urban plans, simplify streets and utilities, etc. The question to rebuild what had been destroyed or build anew was up in the air. Different cities took different tacts. But references to eras past would not necessarily succeed in expressing a new democratic age in Germany. On the one hand, democracy was not triumphant: it was prescriptive. On the other, the styles that normally represented democratic institutions–Hellenic and Roman–had already been exhausted by German historicism. Rather than democracy, the represented beauty and spirit, ideas that had lost credibility to a public that had mentally checked out. Gothic, which might have connected Germany to the past of urban republics, had been swept up by Romanticism. If remembering was painful, history provided no solace. If the past were a source of symbols, the war made them unavailable. Modern architecture was far from being insensitive to the needs of the people. It addressed those needs directly.

Would contemporary Germans recognize this wisdom in their postwar ancestors? The pursuit of unity seems to extend to history as well as geography and demography, seeking out a continuous history of the German people, if not nation. But as I have said before, modernism treats space as disposable, thus modernism is itself disposable.

What's Spanish for Chutzpah?I tend to lose track of time. It’s a bad quality for an historian, but confronting the same boring file for hours speeds the passage of time even though one perceives it grinding to a halt. I had been picking away at the same document today (in between bouts of looking after my son) before I gave up, turned on the TV, and surrendered to the pablum of cable news.

Only I didn’t realize what time it was. Suddenly, the dreaded words, “Lou Dobbs Tonight,” appeared in the bottom corner of the screen. Yes, it was that hour when CNN imitates Radio Rwanda, only tonight the Grand Wizard surrendered his stool for his underling (according to the rumor mill, Dobbs wants to import remnants of the Berlin Wall to southern Texas).

As with any other night, another story about Mexico or Mexican immigrants was being broadcasted. This one carried the title, “Mexico’s Chutzpah.” Unfortunately, it carried the subtitle, “What’s Spanish for Chutzpah?” Some clever tech or intern must have thought that one up on the fly. Did they really mean to destroy the credibility of the news shows raison d’être? Did they know it is a loan word from Yiddish, assimilated by English?

Indeed, what is Spanish for chutzpah? Is Yiddish spoken on the streets of Mexico City or Monterrey? Surely a Spanish equivalent can be found ( atrevimiento?), but chutzpah carries with it an ethnic flavor and a certain demonstrative quality that Spanish words might not have. But perhaps there is some word, based on Hebrew’s contact with Spanish, some bit of Ladino slang that affected Spanish, surviving the expulsion.

Of course, asking the question reflects a certain insolence. Is not Chutzpah evidence how language survives and grows when in contact with immigrants and their culture? Does it not show reveal the success of Jewry in acculturating to American life over generations?

So, if we assume that chutzpah is Spanish for chutzpah, we would reference a successfully assimilated minority. If there is a Ladino-Spanish equivalent, we would reference a successfully assimilated minority that was converted by force, dispossessed of property, and expelled.

Perhaps we could say huevos. It’s already part of American slang.

What I've been doing at Europe Endless

If you haven't switched over yet, do so

now.

Autonomy in the AcademyThe Brussels-based think tank, BRUEGEL, is rankling some feathers with its report on the performance of European universities, “Why Reform Europe’s Universities?” (full report loads in pdf form). According to its methods (which I won’t analyze–note attention to patenting below), American universities perform vastly better than European, with some American states beating out higher education in all European nations.

Explanations focus on spending, especially the amount spent on research. What I find interesting is that the report also focuses on the governance of universities,

noting that administrations of Americans universities have greater latitude in determining how to spend available funds.

There is considerable variation in university governance across states. States vary not only in the relative importance of private versus public universities, but also in the degree of autonomy granted by state authorities to public universities. Sometimes, even neighbouring states display sharp differences in governance. For instance, public universities in Illinois enjoy on average rather low autonomy, while their neighbours in Ohio enjoy high autonomy. These differences are persistent over time and often go back to the idiosyncratic origin of American universities, which in turn reflect differences in the preferences of university founders … .

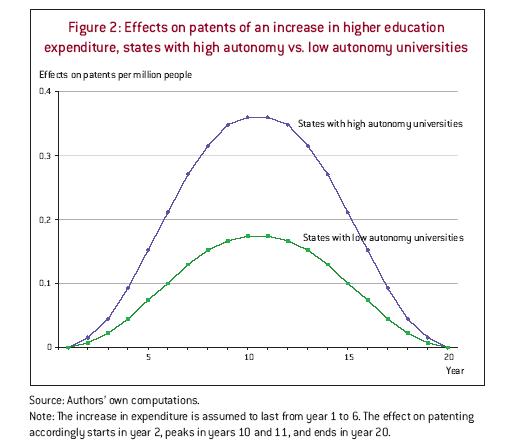

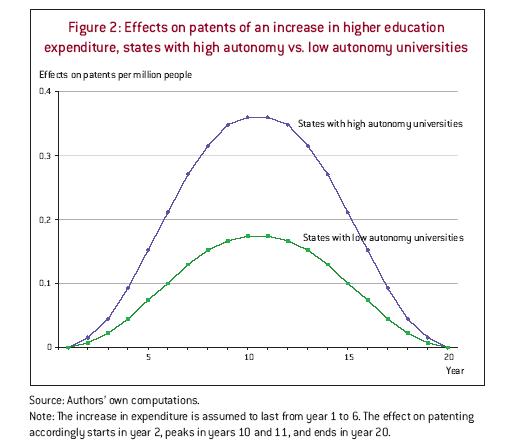

Our strategy is to take US states’ differences in university autonomy as given and then ask the following question: Does a given investment in higher education produce more patenting in a US state if universities in that state are more autonomous? … The answer to our question is a resounding ‘yes’. As illustrated in Figure 2, the effect of additional spending on patenting is roughly twice as high for states with more university autonomy. Autonomy therefore greatly enhances the efficiency of spending.

Limits of Liberal Tolerance?John Holbo, responding to Stanley Fish, wrote the following last week:

I would also like to request a moratorium on critiques of liberalism that consist entirely of a flourish for effect – with accompanying air of discovery – of the familiar consideration that liberalism is inconsistent with blanket, categorical tolerance of absolutely every possible act and attitude. That is, liberalism is incompatible, in practice, with any form of illiberalism that destroys liberalism. If something is inconsistent with liberalism, it is inconsistent with liberalism. Yes. Quite. We noticed.

Also, it might not be a half-bad idea to notice that liberalism is not incompatible with religion, merely with illiberal forms of religion. Just as liberalism is incompatible with illiberal forms of secularism.

Of course, liberalism need not devolve into a celebration of all philosophical systems, all world-views. It’s reasonable to expect that, given liberalism’s attention to the individual, aspects of any philosophy or belief that limits individual action would come under criticism. Certainly liberalism would not seek to become self-defeating. However, Mr. Holbo wants to believe that liberalism is itself intolerant of intolerance, that the compromises made in the midst of political discourse does not undermine the philosophical foundations of liberalism.

Is liberalism intolerant of intolerance? I find it hard to swallow. In practice, liberalism reveals itself as a different beast from its self-image. The history of its application reveals difficulties in accepting completely open political discourse. Liberal political parties started by introducing voting qualification or making elections indirect. Later compromises followed. (I could launch into another long exposition about Jacobins or the Kulturkampf, but I’ve decided not to write about them for the next few months.)

There are two problems: how liberalism constructs its legitimacy, and the makeup of liberalism itself. Tolerance is but one idea that liberals employ to set themselves off against other groups; the dichotomy between tolerance and intolerance is meant to empower the former at the expense of the latter. In the broader sense, liberalism tends to a singular vision of truth which only with difficulty allows plurality in the public sphere. Indeed the pattern of liberal politics, according to Pierre Rosanvallon, has been to introduce “counter-democratic” institutions in the attempt to limit the individual’s free use of political rights.

Liberalism itself is a problematic concept. Some historians have stopped approaching it as a philosophy. Instead they look at the constellation of political, social and economic interests that come to embody liberal politics. In an upcoming book, L’Empire du moindre mal, Jean-Claude Michéa argues that liberalism was primarily an economic phenomenon that developed a complimentary philosophical tradition. Market economy and democratic politics were two aspects–two “translations”–of liberalism, though the former imposed itself on the latter more forcefully. Defending property and economic rights became more central to their programs, and in nations where they were weak, liberals compromised ideals.

Unfortunately, practice must be taken seriously in understanding liberalism. The liberal critique of traditional institutions provided a powerful tool in political reform, even when applied by non-liberal groups. Liberalism itself has had a shakier history.

Letter to a Future Historian

To whom this may concern:

Will an American president ever utter the phrase, “crimes committed in the name of the American people”? After an acrimonious election and faced with concluding a contentious war in Iraq, the public will need some idea, some formula, to move forward.

I doubt this exact phrase will be used, given that it is how Adenauer convinced Germans of their guilt in the postwar era. “In the name of” allowed enough ambiguity as to what role the German public played in Nazism and the atrocities it caused. It allowed them to sense that they were victims as well as perpetrators of the horrors of war. And given Germans reacted better post-WWII than post-WWI, it was a more effective means of dealing with the recent past.

Eventually, scholars turned their attention to the people, much as I expect will happen in American history. After political history has been exhausted, the public becomes a prime target for analysis. First the policy, then the people. You are the first historian to look at the ambitions and fears of Americans in the “aughts,” and your book will rankle those invested in a particular interpretation of the Iraq War, especially its origins. As much as I welcome the change in discourse on foreign policy, it seems that most Americans are running from defeat rather than embracing ethics and responsibility. Few talk of what we owe Iraqis in the longterm. Public complicity is on no one’s tongue.

Until your monograph is published, historians will have focussed on the deception, or in a few cases, uncertainty. They will have focused on President Bush and his administration. Lies are, however, told for war, but they always find an audience hungry to hear them. Who looked for the River Ebro on a map? Why was “remembering the Maine” such a belligerent act? The invasion of Iraq was sold to a public that feared the foreigner, feared the world, and resented so-called friends who would restrain our global initiatives. It was a public that distrusted the UN. It was a public that put Arabs, Muslims and Middle East countries in the same constellation as terrorism. It was a public convinced that behind every major action, there was a state. It was a public whose faith in the war was unshaken by scandals like Abu Ghraib when they were revealed.

You will receive accolades and harangues. Please, though, be kind to us. You are one generation looking back on another. The middle class is always slow to mobilize, and memory takes time to integrate painful images and experiences. Like the young Germans of the 1960s, you will have a perspective borne in distance that helps you see the war.

Good luck, and good sales,

Nathanael D. Robinson

The Great Blog Migration

I've thought about this for a while, perhaps too long, but I am joining the great blog migration and setting up in Wordpress over at some place I call

Europe Endless. Like many migrations, I'll cross vast seas in dangerous vessels, expansive desserts searching for water, before I arrive. So, until October, I'll be posting the same material at both sites as I get the latter set up.

Next month in

europeendless.worpress.com .

The One Who Must Go

It’s been a while since a new addition of Hate Watch. The minor victories of neo-nazi parties in state in local elections were tempered with resolve by the major parties to shut them out of power, to prevent them from exercising any influence. However, the slide into racism is becoming more real, as the Rheinisches Merkur reported this weekend:

A study published last November by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung arrived at shocking conclusions: almost ten percent of western Germans, and more than double that in the east, are antisemitic, every eleventh German has a reactiony (rechtsextreme) worldview, and in the east every third German is a xenophobe. Accroding to a study by the University of Bielefeld, two of every three Saxons holds a xenophobic position. [Despite divergences in the numbers], it is still certain that in the east, people with dark hair run the risk of being attacked. Xenophobia has become the cultural norm. The stranger is the one who should leave.

Racism, of course, often is a stigmatization of the other, the fear of an ideally threating stranger in the midst of an ideally composed, harmonious community. As the article points out, the other are increasingly not present (only two percent of people living in Saxony are of non-German origin). Their foreignness is imagined and constructed far ahead of their arrival, their presence a priori unacceptable.

It would be easy to say that Germans have not changed (even Goldhagen grants them some redemption). Racism, however, is not just finding new targets, it is behaving differently. The German racist is evolving into an advanced scout announcing a fantasy enemy. Resentment plays less of a role in his/her make-up. Correspondingly, the reaction of Germans to reactionary racism is remarkably different. If xenophobia is becoming the norm, resisting it has become a necessary and automatic response for the German public.